One of my favorite Instagram follows is @streetrepeat, an account created and curated by photographer Julie Hrudová, where she posts images by street photographers that revolve around the same theme. The concept, explained on the project’s website, is simple enough: “StreetRepeat is an Instagram account that focusses [sic] on repetition and similarities in street photography. It is born out of a fascination for the amount of repeated patterns in street photography, particularly on Instagram.”

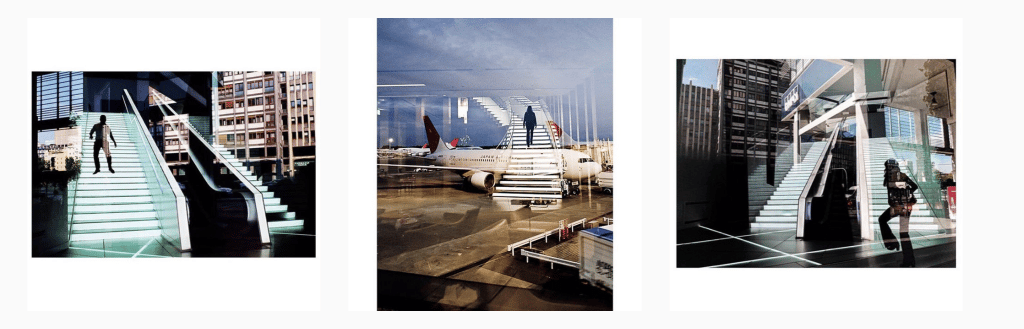

A selection of images around the theme of “reflecting steps” from @streetrepeat’s timeline on Instagram. (L to R: Stuart Paton, Jack Simon, Valeria Cammareri)

Hrudovà’s curation is astute in choosing images that aren’t necessarily composed similarly, but rather, focus on using the same technique, subject or approach. What’s fun about following the account is that, even though the photos were created independently, presenting them in sequence makes it seem like a single idea was commissioned out to different photographers, not unlike a homework assignment or a skill challenge.

Of course, that’s not really the case. For all I know, the similarities and patterns are completely coincidental, and there is no indication that the images draw inspiration from the same source. But regardless, the similarities are striking, and seemingly, almost too coincidental.

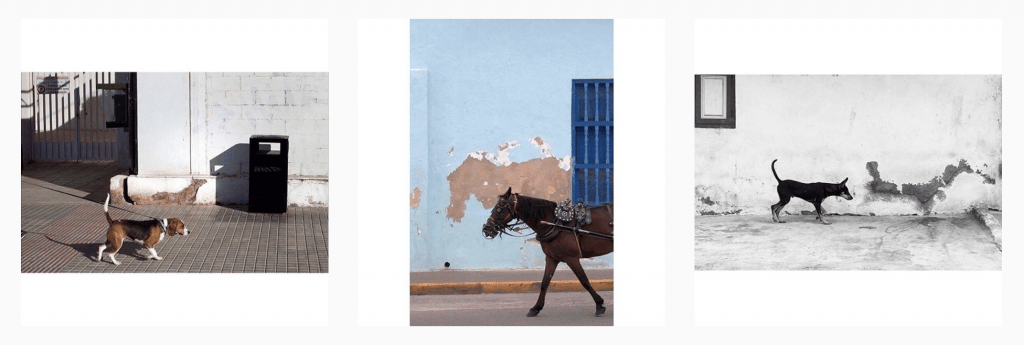

Separate photos around the theme of “when a wall copies an animal” posted on @streetrepeat. (L to R: Peter Kool, Dash Izari, Viduthalai Mani Dharmaraj)

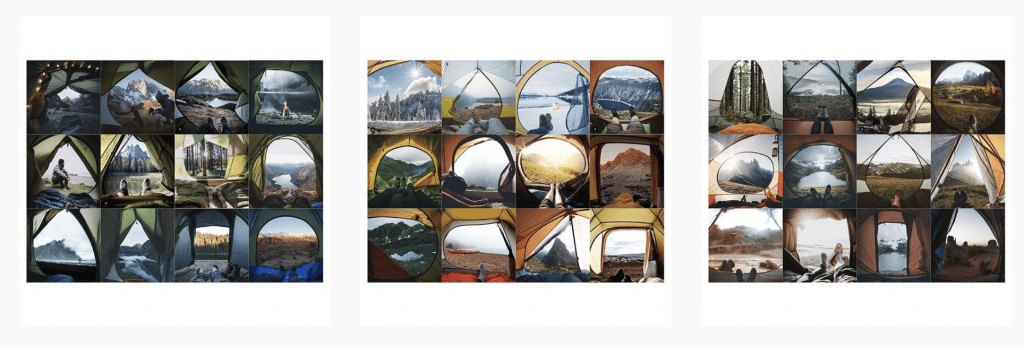

StreetRepeat isn’t the first or only Instagram account based around the concept of repetition. The hugely popular @insta_repeat is similar in nature, exposing “déjà vu vibes” and the generic quality of Instagram photography, where every image seems like a copy of a copy, devoid of any creativity or fresh thinking.

A host of images all taken in the same location, in the same manner, as posted on Instagram account @insta_repeat.

Insta Repeat posts collages of photos from the same geographical location that look remarkably similar, even though they were taken by different photographers.

The account lampoons the recent boom of so-called “Instagram tourists”, where prominent and aspiring influencers travel to the same locations in order to replicate Instagrammable moments to share with their audiences. They collect images of dangling feet at Horseshoe Bend and long-haired women paddling boats in mountain lakes like they’re numbers to mark off on an influencer bingo card.

While StreetRepeat and Insta Repeat are similar in concept, I do think there is a key difference between them. Whereas Insta Repeat seems to be making the point that what gets passed off as creativity on IG is actually cheap imitation, StreetRepeat seems to make a different point altogether—that photography, like any artistic form, is built upon a common inspiration, an almost divine influence that affects us all, and to which no one is immune.

This got me thinking about those two concepts—imitation and inspiration—and, ultimately, what are the differences between the two?

Intention Matters

You could say that the biggest difference is born out of intent. When someone aims to imitate, they simply want to make a copy. They study the elements that make up a photo—how it’s composed, constructed and edited, for example—and try to replicate it as accurately as possible, not straying from the original concept.

The intent on Insta Repeat is deliberate—to duplicate a photo in order to evoke a similar response from viewers.

Feet dangling over Horseshoe Bend evoke a sense of adventure and thrill-seeking. The woman paddling in a mountain lake evokes wonder and serenity. So, if you want to conjure those emotions in your audience (while also projecting those qualities onto yourself) just retrace the steps, and—voilà—success! Follow the formula and you’ll achieve similar results.

Is it cheap to just blatantly copy something? Yes, undoubtedly. But is it any less effective if the viewers don’t know/don’t care? Probably not. So, it’s easy to see why this practice is so prevalent on social media. And I can’t help but note that it takes some amount of skill to be able to replicate an image. You at least have to be able to recognize what makes the original image impactful before you can aim to copy it.

The “looking out the tent hole” trope exposed on @insta_repeat.

When someone is merely inspired by an image, however, the intent may not be clear. To be inspired is to take an idea from an outside source and apply it to your own work. But, heck, it’s entirely possible to be inspired by something without even being conscious of it, so intent gets a little murky.

This is illustrated in the classic case of the George Harrison song, “My Sweet Lord”. Harrison was sued for blatant melodic similarities in his song to an earlier tune called “He’s So Fine”. Ultimately, Harrison was forced to share royalties with the original songwriter, but the interesting part is that it was argued in court that the ex-Beatle copied the song subconsciously—meaning that while he was certainly aware of the song, he didn’t outwardly set out to imitate it—it just happened subliminally. The melody was in Harrison’s head, but it was unclear to him how it got there until the similarities were pointed out.

Of course, in the eyes of copyright law, intent doesn’t really matter. But what about outside the law? If we seek to evoke a similar response in our audience, does it matter to what degree we copy from the original work, what our intent was, or if we were even aware that we were copying? Ultimately, is inspiration just a covert form of imitation?

The Pattern Is Full

To examine this, we should probably talk about how our brains deal with pattern recognition, and, let me put out a disclaimer—I don’t claim to be an expert in this field, so I’m going to keep this real high-level.

To my understanding, there’s a stage in our early brain development where something called Seriation happens. Seriation is our ability to arrange items in a logical order along a quantitative dimension—the triangle block fits into the triangle hole, the yellow ring goes on the yellow peg, the interlocking jigsaw puzzle pieces make a complete picture, and so on.

Seriation and pattern-forming in practice.

Turns out, humans are extremely good at this type of logic. It’s what sets us apart from most other animals, and it makes us particularly good at problem-solving. We are pattern-recognizing machines. And our ability to store short-term pattern information into our long-term memory is what makes things like recognizing long-lost friends, learning languages, and even appreciating music possible.

Once you grasp that, it’s not a stretch to understand that our ability to recognize visual patterns in everyday life is part of what makes us good photographers. And while some people are more adept at this than others, an eye for composition, juxtaposition or arrangement are skills that can be learned through practice and study, and they’re not exclusive to a select few.

So, if we’re all capable of pattern recognition, and we all inhabit the same world, then it’s unavoidable that different people will recognize similar patterns. It’s inevitable that the same themes will be arrived at by people who have never seen each other’s work. In this case, inspiration is not drawn directly from someone else’s work, but from our own desire to arrange things in a logical order—a sort of uber-inspiration—or that divine influence i spoke of earlier that affects us all.

Back To Reality

So, before I risk losing myself any further in this topic, let’s bring it back to those accounts I follow on Instagram. Obviously, Insta Repeat is a great example of how imitation left unchecked can result in homogenous, manufactured images, devoid of any originality. When it comes to StreetRepeat, however, it’s a different type of repetition on display. I think there’s a bit of serendipity and providence at play there, illustrating the commonality of our human experience and that we’re all drawn to similar patterns, driving us to make similar images.

Don’t get me wrong, there are probably clear cases of imitation there as well, and I’m not trying to say that street photography is immune from “déjà vu vibes”, because nothing is further from the truth. Most of street photography shared on Instagram is derivative and tropey, like any other genre. I’m guilty of it myself. I’ve definitely got into people’s faces with off-camera flash and a wide-angle lens to try my hand at a Bruce Gilden shot, or framed a silhouette through foggy glass to achieve a haunting Saul Leiter vibe.

My own photography has certainly drawn inspiration from William Klein’s “pseudo-ethnographic, parodic, Dada” work.

But my point is that, ultimately, imitation and inspiration are not that different. They all seem like fundamental steps in finding our own style, and making work that others will respond to. The danger is in not recognizing what’s influencing you, and misrepresenting someone else’s work as your own invention.